There is a rigor to scientific work. For intervention studies, these research guidelines have primarily been derived from the pharmacological literature. Subject blinding, randomization, careful description of the intervention and protocol should allow future researchers to repeat the experiments and allow clinicians to incorporate the best evidence into clinical practice. In the physical therapy and clinical environment, the results of these studies are used to drive clinical practice, develop evidence-based guidelines and they even form the basis for reimbursement. These studies have the potential to change what we do and if we get paid to do it. In the presence of well-conducted studies, this will change our practice for the better. However, when the study design or conclusions from research study are inappropriate, overstated or just plain wrong, the findings from the research report can change the practice for the worse.

Most, if not all, physical therapy students partake in a research course as part of their PT curriculum. While we certainly do not expect the majority of students to become primary researchers, this course should 1) prepare PT students to become careful consumers of the literature and 2) inform students how to integrate research results into clinical practice. When working with my graduate students in the lab, we review high quality articles in journal club. However, I also feel there is a particular benefit from reviewing articles that have significant flaws. The ability to identify these flaws improves their writing and allows them to discriminate good vs poor research quality in the clinical and research environment.

Below are three articles that I think fall into the poor quality for specific reasons. While the research question itself is appropriate in all of the articles, several issues are apparent. This is not meant to be a rant, but I think that students and clinicians can learn a lot by reading papers that leave out important details. If you have trouble accessing these papers to read for yourself, let me know.

Paper #1: No need for outpatient physiotherapy following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial of 120 patients.

Rajan RA, Pack Y, Jackson H, Gillies C, Asirvatham R. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004 Feb;75(1):71-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15022811CONCLUSION: “…inpatient physiotherapy with good instructions and a well-structured home exercise regime can dispense with the need for outpatient physiotherapy.”

THE PROBLEM: The primary concern I have with the paper is that the conclusion, which is explicitly stated in the title (No need for outpatient PT after TKA), is substantially overstated. There are two reasons this conclusion is not in line with the findings.

First, you cannot conclude that there is no need for outpatient physical therapy when the only outcome measure assessed was knee flexion range of motion. Outcome measures must be directly related to the dimension of recovery that the clinician is attempting to evaluate. Surgeons have notoriously evaluated outcomes after TKA, and more importantly the need for post-operative rehabilitation, based solely on knee flexion range of motion (Mockford, Thompson, Humphreys, & Beverland, 2008; Rajan, Pack, Jackson, Gillies, & Asirvatham, 2004), a single clinical metric that has little relationship to functional capabilities (Jones, Voaklander, & Suarez-Alma, 2003). Strong conclusions, such as “no need for outpatient physiotherapy following total knee arthroplasty” are misleading and unjustified when knee flexion angle is the only outcome measure upon which this conclusion is based.

Second, physical therapy is not a singular “thing.” If you are comparing a treatment to physical therapy, you have to describe the duration, frequency, specific exercises and rate of progression. I can’t imaging performing a drug trial and not describing the dose, frequency or method of administration! There is no description of what the physical therapy consisted of in those randomized to the PT group, except that outpatient PT was usually given 4-6 times after discharge from the hospital. YES….you read that right. Some patients in the PT group only received 4 outpatient PT sessions. Is there any surprise that there was no difference between groups in range of motion 6 and 12 months after TKA? Well I am certainly not surprised that the average knee flexion range of motion in both groups was less than 100 degrees!

THE BOTTOM LINE

- Inappropriate outcome measure

- Conclusion is not supported by findings

- Both groups under-rehabilitated (less than 100 degrees of knee flexion)

- PT program was not based on best evidence (some may have only received 4 PT sessions, although to the author’s credit, most of the evidence supporting more aggressive PT protocols after TKA has only come out recently)

Paper #2: Internet-based outpatient telerehabilitation for patients following total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial

Russell TG, Buttrum P, Wootton R, Jull GA. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011 Jan 19;93(2):113-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21248209

CONCLUSION: The outcomes achieved via telerehabilitation at six weeks following total knee arthroplasty were comparable with those after conventional rehabilitation.

THE PROBLEM: The authors state that rehabilitation after TKA done with the aide of interactive web-based technology was not different from clinic based rehabilitation. Again, the authors use “standard physical therapy” as a control group. They describe there PT protocol as follows:

“Rehabilitation for the control group was administered in an outpatient physical therapy department, according to standard clinical protocol. Intervention sessions were limited to forty-five minutes, during which the physical therapist administered an appropriate assessment, treatment techniques, and exercise interventions within the bounds of the local postoperative guidelines .”

Local post-operative guidelines. Hmmmmm….that should say “using evidence-based rehabilitation techniques described here, or here, or here.” Although the authors do not report the actual outcomes at follow-up (they report the change scores), both groups again appear to be under-rehabilitated. On average, both have knee flexion contractures and were still unable to do a straight leg raise without a quadriceps lag indicating significant residual weakness. The real take-home clinical conclusion should be “Neither intervention eliminated impairments related to functional performance.”

I have nothing against tele-rehabilitation, so long as it works and is used with appropriate patients, in an appropriate setting with appropriate reimbursement for the rehabilitation professionals who lead telerehab care. In fact, I had a student who did an independent study examining how we can use gaming equipment such as the Wii or XBox Kinect to monitor or oversee patient care in the home. There is a lot of interesting tech-breakthroughs that are just over the horizon.

There was a commentary posted about this article that mentions some of the weaknesses. However, I think that even this commentary overlooks some of the more major limitations of this paper. (Commentary by Dr. Allen Gross can be found here.)

THE BOTTOM LINE

- No description of the physical therapy intervention

- Outcome scores at follow-up were not reported

- Both groups appear under-rehabilitated

- The home environment of the telerehabilitation group was simulated in a hospital (although the authors acknowledge this limitation)

- No description of the cost associated with telerehab, although the authors make a case that this will save money compared to conventional PT

Paper #3: Comparing Conventional Physical Therapy Rehabilitation With Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation After TKA.

Levine M, McElroy K, Stakich V, Cicco J. Orthopedics. 2013 Mar 1;36(3):e319-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23464951

CONCLUSIONS: “The results suggest that rehabilitation managed by a physical therapist results in no functional advantage or difference in patient satisfaction when compared with NMES and an unsupervised at-home range of motion program. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and unsupervised at-home range of motion exercises may provide an option for reducing the cost of the postoperative TKA recovery process without compromising quadriceps strength or patient satisfaction.”

THE PROBLEM: When I first read this paper, I was exceptionally concerned. Here is a paper that concludes that there is no difference between PT done in the clinic vs. a NMES performed unsupervised at home. Interesting. However, it was impossible to draw any conclusions from this paper because of several methodological omissions. In particular, the dose, duration, frequency, parameters in both groups were not provided! If a drug trial was submitted for publication without this information, it would be immediately rejected. Why should any other study not be held to these basic standards. No conclusion can be drawn from this study, except that it appears that both groups were under-rehabilitated at the end, with low KSS and WOMAC scores and knee flexion contractures.

Only when the best clinical physical therapy practice is compared to non-supervised treatments can any conclusion about the effectiveness of non-physical therapy regimens be discussed. This is not a trivial consideration. Peer-reviewed and published articles are used to make decisions about clinical practice, reimbursement and plans of care. We need to do better as rehabilitation and medical communities to ensure the details of our work are appropriate and the conclusions reflect the actual methods of the study. A pharmaceutical trial would not make it to the peer-review process in the absence of information pertaining to the dose, duration or method of administration. The same standard needs to be adhered to for all areas of healthcare research.

This brings up the second issue with the paper. When comparing physical therapy to a non-physical therapy protocol, it is essential that you use best practice in the comparative group. This problem prompted me to write a letter to the editors in which I described the concerns about the lack of detail and the use of a substandard rehabilitation protocol (plus some additional concerns). The excerpt on the right is from the conclusion of that letter and sums up my concerns with poor quality healthcare and physical therapy research. I will update with a link to the full letter when (and if) it gets published.

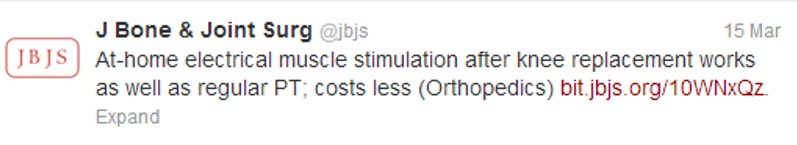

The problem with this type of research is how fast the conclusions can be distorted and disseminated. Look at the following tweet from JBJS. Keep in mind there was no cost analysis in this study and there was no description of what ‘regular PT’ was. In the abbreviated vernacular of this communication format….smh

THE BOTTOM LINE

- Lacks sufficient description of intervention

- Inappropriate outcome measures (Strength not an outcome even though using an intervention specifically designed to modify strength)

- Comparative physical therapy protocol was not based on best-available evidence (Both groups are under-rehabbed 6 months after TKA)

These articles are used to drive patient care, determine treatments eligible for reimbursement and underlie clinical decision making. As researchers, we need to write appropriately and provide all of the facts. As clinicians and consumers of these papers, we need to be able to discriminate optimal methods and appropriate conclusions from sub-par research reporting.

–Written by Joseph Zeni, Jr. PT, PhD (These views are my own, but I think you would be hard-pressed to find other rehabilitation researchers and clinicians who don’t agree!)

Courtney Mezzacappa, PhD

Mar 27, 2013 -

I completely agree! Great blog, and great post!

Ross Haley, PT, DPT, GCS

Mar 27, 2013 -

Well said, Zeni

Joseph Zeni

Mar 28, 2013 -

This post uses total knee replacement as a model, but this type of research and reporting is pervasive throughout rehabilitation research. My concern is not so much that a clinician will read this article and misinterpret or be overwhelmingly swayed by the findings, but rather that the media, third-party payers and non-rehabilitation clinician/scientists will read these abstracts and run with the overstated conclusions. We see this all the time, the JBJS tweet is just one example. When searching for these articles in Google there were several online and mainstream news publications that reported the conclusions from the authors, with no comment about the quality of the work.